Author Archives: sarahashelton

Composite

Desk

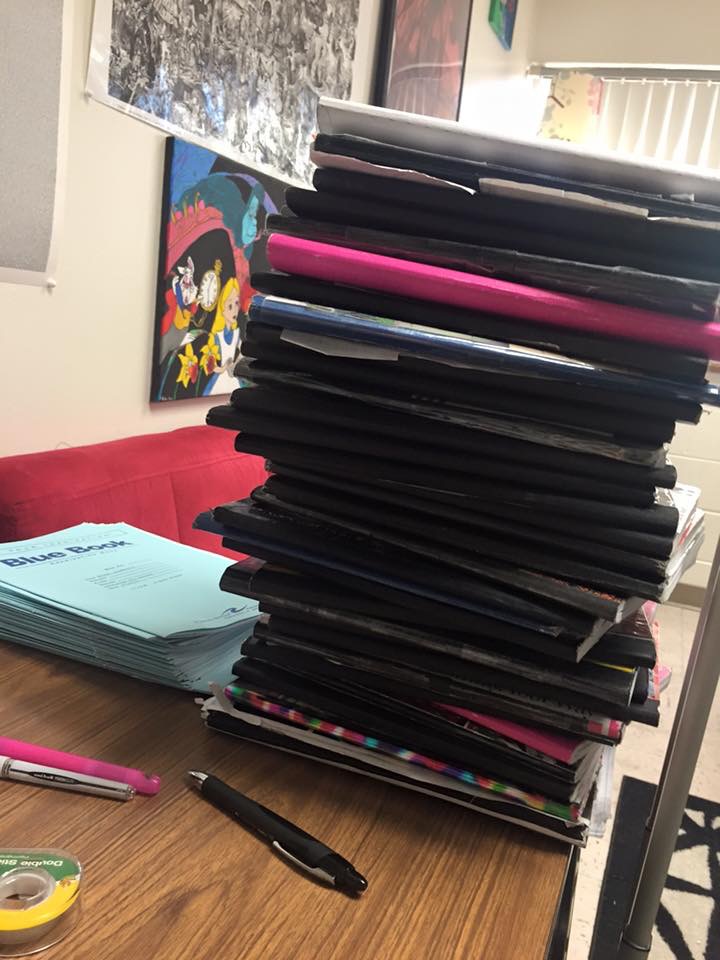

Grading ~ Mariboho/Shelton Office, CARH 402 ~ Midterm

I should feel ecstatic for plowing through this round of journal checks in a single afternoon. Instead a fresh stack of Blue Book midterms mocks me and Blackboard awaits with several columns of exclamation points. #treading #donthavetimetobesick

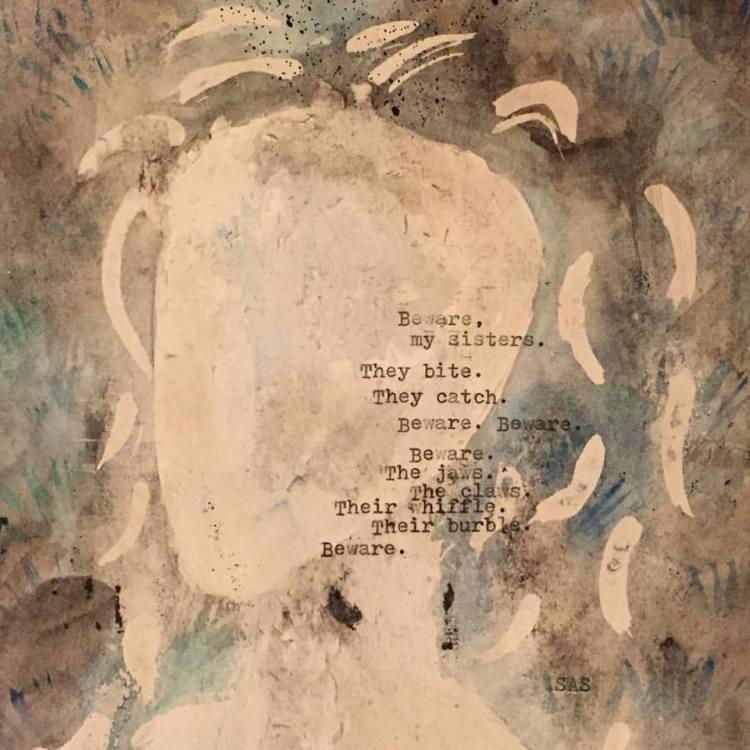

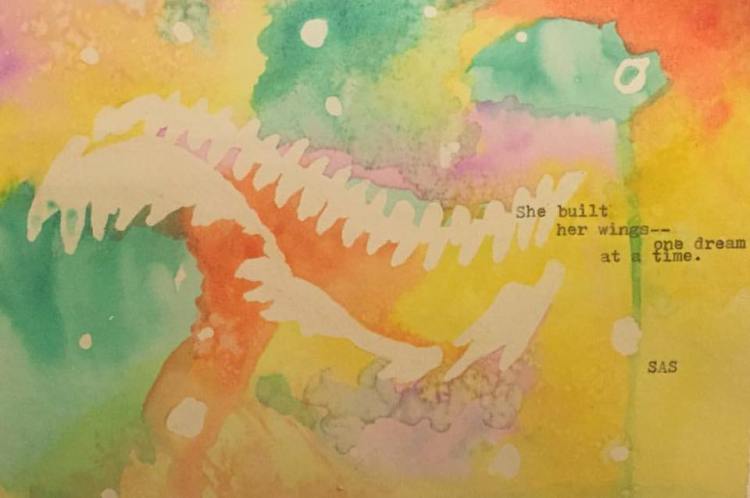

WORDS/MATTER

Writing to Eleanor, age 1.

#snailmail

Excerpt: Article Published in Fat Studies Journal

Introduction

For too long, scholars and critics not working from a fat studies perspective have celebrated novels that feature fat teens losing weight and finding happiness and self-worth only because of that weight loss. Indeed, in her article, “Voracious Appetites: The Construction of ‘Fatness’ in the Boy Hero in English Children’s Literature,” Jean Webb analyzes fat character’s “lives [as having] the potential to expand positively as their waistlines recede healthily” (119) (my emphasis). The “as” in Webb’s analysis is key to revealing the ableism and fat bias inherent in U.S. society in general and in Webb’s argument in particular. Fat studies, however, reveals that the “Bildungsroman of weight loss” that Webb valorizes is far from being the positive and pragmatic solution she characterizes it as. Instead, working from a fat studies perspective, I claim that when a quest structure melds with the cosmetic panopticon, we get what I call “the fat quest” (see Fig. 1), a culturally constructed set of steps a fat protagonist must take before he/she can be considered worthy. Recent novels like My Big Fat Manifesto or Eleanor & Park positively challenge the fat quest, breaking its pattern or excluding it altogether. But if we are to help youth find worth outside of a qualifying “as,” it is essential that scholars stop arguing from ableist perspectives and begin celebrating and empowering critique and literature that reads positively through a fat studies lens.

[…]

The Fat Quest

While a “Bildungsroman of weight loss” can exist—and be praised as positive—in ableist discourse, a body-positive, fat-acceptance discourse doesn’t accept or ascribe such a benign-bordering-on-positive name to such structures and strategies. They are better called and understood as a “fat quest,” a path—assigned by a thin-centric society to fat people—that characters must follow in order to illicit empathy, understanding, and to even be considered human. The fat quest is, then, a culturally constructed set of steps that must be taken before a fat protagonist can be considered human enough, thin enough, and worthy enough of dreams and quests that “normal” teen protagonists get to undertake. And though the fat quest promotes ableism by tying health and worth to weight via fat bias, understanding its structure, breaking it down, and reframing it as one version of instead of as the YA fat fiction genre itself opens up a space for authors, scholars, and readers to challenge ableism. Such is the power of genre—texts mix and mingle via uptake and help disparate readers enter the discourse through shared expectations while encouraging the questioning of ideology through reversals and gaps.

In the U.S., we love a good quest. It’s an old genre, but one that we readily recognize and understand. After all, the American Dream is a quest, a journey from nothing to something typified by our national mythology of the “self-made man.” The American Dream, in fact, demands willpower and scorns those too “lazy” to make their dreams come true. This quest structure, then, melds with the “cosmetic panopticon” (Giovanelli & Ostertag 2009:289), 4 a prison of our own making, powered by our media’s consistent and exclusive casting (e.g., in literature, movies, television, theater) of fat people in the roles of “the old, the ugly, or the comical” (Jester 2009: 249). Our teens must “[navigate] puberty’s mysterious turf” with the help of this media that celebrates an ideal that “can only be attained by the thinnest 5% of the population, thus, oddly consigning the majority to outsider status” (Glessner et al. 2006: 117). They quickly learn that their bodies are “the ultimate expression of the self” (Brumberg 1997: 97) and that “fatness in the United States ‘means’ excess of desire, of bodily urges not controlled, of immoral, lazy, sinful habits” (Farrell 2011: 10). Indeed “much more than a neutral description of a type of flesh, fatness carries with it such stigma that it propels [teens] to take drastic, extreme measures to remove it” (Farrell 2011:10). And, as The Biggest Loser, as diet ads, as One Fat Summer teaches teens, fat characters can be “good”—they can get the girl or boy, win the prize, stop the bullying, save their family, earn respect—if, as their extreme measure, they go on the fat quest. Unfortunately, such diet measures rarely work outside of marketing and fiction and readers are left wondering why they cannot achieve a similar “magical” transformation 5 and left believing that they are even more worthless than before (Bacon & Aphramor 2011).

As I’ve outlined in Fig. 1, Robert Lipsyte’s(1977) One Fat Summer is the quintessential fat quest tale, his protagonist, Bobby Marks, the negative baseline against which I measure the positivity of the portrayal of other fat protagonists. First published in 1977, One Fat Summer follows Bobby Marks’ summer fighting bullies and his own body only to come out the winner and, more importantly, thin. He is celebrated for this weight loss; it solves his problems. His journey, as Fig. 1 shows, consists of nine steps that become the defining structure of a pure fat quest tale, a structure which drives all character and plot development, a plot that teens easily recognize and can predict the outcome of—the character will live thinly ever after.

© Taylor and Francis: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21604851.2016.1146117

NYC II

We go dancing at the Pyramid Club. 80s Dance Party night. We aren’t the oldest there; we aren’t the youngest. Laid by James is the first song I really let go to—arms wide, head back, eyes closed, hair swinging, full-body singing, singing, singing…. “This is my favorite”—or something along those lines—shouts the one in our group who says she never dances (she’s the one we have to drag off the dance floor and into a cab at some early morning hour, and still, today, she insists “she doesn’t dance”). There are oceans of clear space between the huddled pods of dancers. A line of youngish (younger than me at least, and at 35 they all look young to me now, babies playing at loving the 80s. Sweethearts, these songs are my childhood…) white dudes holding up one wall, all of them staring at their phones. A mix of genders on the other wall, crowding ‘round the projected 80s logo for a selfie to prove their kitschy hip. And for a second I wonder why they came—why bother?

But then another memory dressed in the lyrics of another familiar voice hits the air and one or more of us shout “This is my favorite!” before we’re lost to our own moves and time passes one song at a time until those oceans tide over to people, jumping-singing-dancing-laughing bodies all up and down every identity spectrum you could name.

We dance. All in different ways. All for different reasons. I don’t have to name mine—couldn’t put my fingers on them to type out the words perfectly anyway. But I’m my sequined top and leather jacket and boots. Glitter, grit, and mirror ball, light pulsing in the fog-machined dark. All the different permutations, stages of me that have danced, free on the floor like always in the water but rarely on land, all rolled into one. Bass-beating-blood and hard-won-sweat. Full-body singing, singing, singing. Gorgeous as the bouncer said.

Prince shows around midnight—some cos-playing womanizer dressed in the iconic white suit, no shirt, smooth-shaved chest. Sexing up all the youngest ladies while his lumberjack wingman—dude’s well over six-feet, beard, honest-to-god flannel, as un-princely as you can get—watches the hunt like a hyena in the wings (there might be slobber; there’s certainly awe). But everybody loses it, loves it, when cos-play Prince gets up on stage when the DJ plays his song, pulls a purple guitar from the shadows and proceeds to gyrate, drop-split, strip-tease for the crowd. He cheeses me out. Prince-lite, strutting like the man himself, but I’m outvoted—the crowd, my group loves him.

Still, it strikes me, remember-writing-living this again now, that then, with my arms wide, head back, eyes closed, hair swinging, full-body singing, singing, singing…that could have been the real Prince—if I dance-dreamed just right. But now, death’s closed the door on possibility and the remembered flash of sex-and-song through the strobe-and-fog is wrong even in this light.

NYC I

Sitting here, outside the stage door, is like sampling the whole world at once—all the languages, all the potentials.

And in the distance the flashing of billboards and electric lit signs—the trash is out for the night, huge piles of black and white and blue bags stuffed and piled waist high down the curb on both sides.

And the song of car breaks and horns; the delivery truck idling across the street; suitcases rolling along the pavement.

And the car radios tune in an out of a million different stations that touch me—all—before flitting off again.

I could have been anyone who’s passed me by but I wasn’t. I’m not.

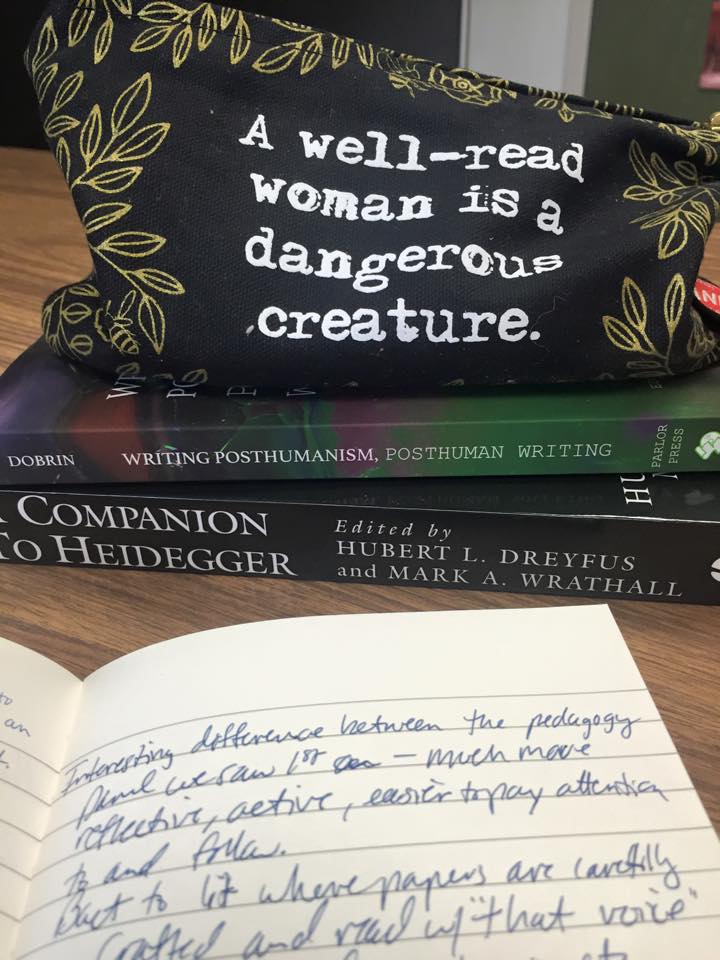

Desk

A Gift ~ Carlisle Hall 205 ~ March 7, 2016

Desk

Organize ~ AD of FYW Office, CARH 205 ~ Monday

Really, the only fun thing about Mondays is getting to rip off last week’s to-do schedule and seeing the pristine cheekie-chokiness of a blank week awaiting filling. And this week, the first task on the list–go to SLC!!! This is not a bad thing to have to do.

Acts of Being

I love a perfect drive. In golf, at least for amateurs (and I’m a level even below that), you hit the ball, one shot at a time down the fairway, each shot a means to the green. But there are, at least for me, some shots, some moments that are perfection. Sweet. Unreal in how incredible it is that I took this club and hit this tiny ball and it went right where I wanted it to go. Hundreds of yards away. And when I played regularly those were the moments I played for. The drive that sailed, that landed right where I wanted it to go. It always amazed me how I came out of those swings not able to describe what went right. There was either in the swing or out of the swing. And once out of the swing, there was no way to recreate in words the seamlessness, the perfection, the resonance of that moment.

Continue reading